|

So far this winter we have only had a couple of days of winter climbing. It has not been very cold and we have had little snow. Next week might turn out to be a little bit colder. There is a layer of snow on the tops right now, and at the end of the week it could get properly cold for the first time. So, here's what to look out for when it gets cold again. We will need to wait a little longer for the different types of ice climb we enjoy in Scotland Mixed climbing has always been pursued in Scotland but it has become more popular in the last couple of decades. Whereas in ice climbing there is a limit to how hard it gets due to the nature of how ice forms, in mixed climbing there is virtually no limit. What is possibly the hardest naturally protected winter climb in the world is found on Ben Nevis; Anubis, climbed by Dave MacLeod and repeated twice since. Greg Boswell McInnes made the third ascent in 2019, a particularly poor winter for climbing. This illustrates the attraction of mixed climbing, that good climbing conditions can form quickly and there is ample opportunity for a challenging climb! In the same way as with ice climbing, judging the nature of the climbing conditions is a tricky job and one that demands dedication, time and many attempts, both successful and unsuccessful. Once you know what to look for and how the recent weather affects the climbs, you will be able to make better decisions. Mixed climbs need to be white and frozen to be in generally acceptable condition. Dry tooling is not acceptable on Scottish crags away from some low level training crags. In the mountains, the crag needs to be be wintry in appearance, white with snow or rime and frozen. This is the ethical approach that has developed over many years and is peculiar to Scotland. Many foreign climbers are baffled by these restrictions, but we abide by them to maintain the quality of experience and so that we are all playing by the same rules. Waiting until the crag is properly frozen also protects turf from excessive damage. Different types of mixed climbs might be termed snowed up rock climbs, turfy mixed climbs or true mixed climbs on which a mixture of rock, turf, snow and ice is experienced. All of these types of route need to be well frozen to give good climbing. Snowed Up Rock Climbs. Snowed up rock climbs can freeze first due to being mostly made of solid rock. Even so, blocks, chockstones and flakes need to be frozen in place, and this takes a couple of weeks of sub-zero conditions at the start of the winter. They often make a good choice for the first climbs of the winter season because they are first to freeze, don’t require any thaw freeze cycles and can offer reasonable protection. “Snowed up rock climb” is actually an unhelpful name for this style of climb. It is rime that is more effective at making the climb white and that will provide better climbing conditions. Rime is a type of ice crystal that grows on any surface exposed to humid air being blown onto it in a sub-zero temperature. It is often seen on fence posts and, perhaps confusingly, grows into the wind. So, you need a wind blowing cloud on to the crag and the temperature to be below zero. No snow fall is required at all. After a westerly gale, choose a crag that faces west and has been in the cloud. The best conditions in which I’ve climbed snowed up rock have included really well frozen rocks and a light rime of a couple of centimetres that is easily brushed away to reveal (hopefully) cracks and ledges underneath. The crag was totally white at the start of the day but the climbs were brushed free of rime by climbers on various routes. Delicate dry rime can fall off the crag in a strong wind and is likely to fall off in very dry, cold air. This means that the crag can be white one day but black the next day despite the temperature staying below zero. Once the crag is out of the cloud the rime will start to deteriorate. Sunshine will also strip rime from the rocks faster than you can climb them! However, rime can grow to be a metre deep and turns very icy if it experiences thaw freeze cycles. The summit observatory ruins on Ben Nevis often have incredibly thick rime ice all over them in March that has built up over the previous three or four months and survived many thaw freeze cycles. This is not good to find if you want to climb the rock underneath. In thick, icy rime, it can be a monumental struggle to clear the rime off the rocks for the whole pitch. Thaw freeze cycles will also create dribbles of water that run into cracks and refreeze. Iced up cracks are a problem; finding pick placements can be very hard and uncovering protection incredibly tiring. Snowed up rock climbs are best early in the season when the cracks are still clear of ice and the rime is light and fluffy. Snow fall can also make a crag white in appearance. Cold, dry snow will not stick to the rocks. It will pile up on ledges making the crag look white from above but not from below. If the snow is a bit wet (this happens when the temperature is at or not far below freezing) it can stick to the rocks and make the whole crag go white. This wet snow can also freeze into an unhelpful icy crust which is hard to clear from the rocks when you are climbing. Some snow on the ledges is very often a helpful thing to have on all mixed climbs, including snowed up mixed routes, especially once this snow has transformed into solid snow ice after a freeze thaw cycle. Curved Ridge on Buachaille Etive Mor, Crest Route on Stob Coire nan Lochan, Slab Route and Gargoyle Wall on Ben Nevis are all excellent snowed up rock climbs. Turfy Mixed Climbs. Turf freezes slowly. Small tufts of turf freeze first and freeze most quickly when they are exposed to a cold wind. Wind chill affects the crag in the same way as it affects us when we are exposed to the wind. Big patches of turf can take many weeks to freeze properly but can be damaged or even completely removed from the crag if they are climbed over before they are frozen. However, once properly frozen, turf will stay frozen through some quite substantial periods of thaw. It will hold water in a thaw which will dribble down below the turf and freeze into ice of one sort or another in the refreeze. So, turfy mixed climbs can become really quite icy over the course of the winter. There is nothing more satisfying than placing a pick in a solid, icy lump of turf! Turf commonly holds snow on top of it which is transformed into snow ice with thaw freeze cycles. So, turfy mixed climbs quite often turn into true mixed climbs over the course of a good winter, with a mixture of turf, rock, ice and snow ice. Turfy mixed climbs, like any mixed climbs, should look wintry and white. Rime and snow should cover the rocks. There is an argument that only the turf needs to be frozen and icy, that the rocks don’t need to be white as well since they are not used for the climbing. This is mostly the case on sandstone crags found in the far North West and is also a matter of opinion. It would be easier to say that all mixed climbs need to be white and wintry in appearance with the rocks covered in rime or snow. Morwind is a very good turfy mixed climb on Aonach Mor which changes in character to a true mixed climb and can actually form so much snow ice that you don’t need to use the rock at all. Thompsons Route on Ben Nevis is the same but it requires some snow ice to be formed before it is fun to climb whereas Morwind is good fun as a turfy mixed climb with no snow ice. Taliballan on Stob Coire nan Laoigh is a wonderful turfy mixed climb that turns into a brilliant true mixed climb with varying amounts of ice and snow ice depending on the nature of the storms of the winter. True Mixed Climbs.

Those routes that demand a specific combination of snowed up rock, frozen turf and ice of various kinds are true mixed climbs. Being so specific in nature and requiring the perfect combination of factors in the weather over the course of a couple of months, these are highly sought after climbs. Gemini and The Shield Direct on Ben Nevis are perhaps the best examples. The first few pitches are on steep ice formed by melting snow patches above providing water to freeze into cascade ice. This is followed by a mixture of snowed up rock, snow ice and little bits of turf in the upper pitches. So, now you know what is required to form good mixed climbing conditions, hopefully you will have more success in finding them. You still need to know or to assess the nature of each climb (if it is a snowed up rock route, turfy or true mixed climb) to determine whether it will be a good choice on any given day of climbing. For the moment, you'll need to work this out by yourself.

0 Comments

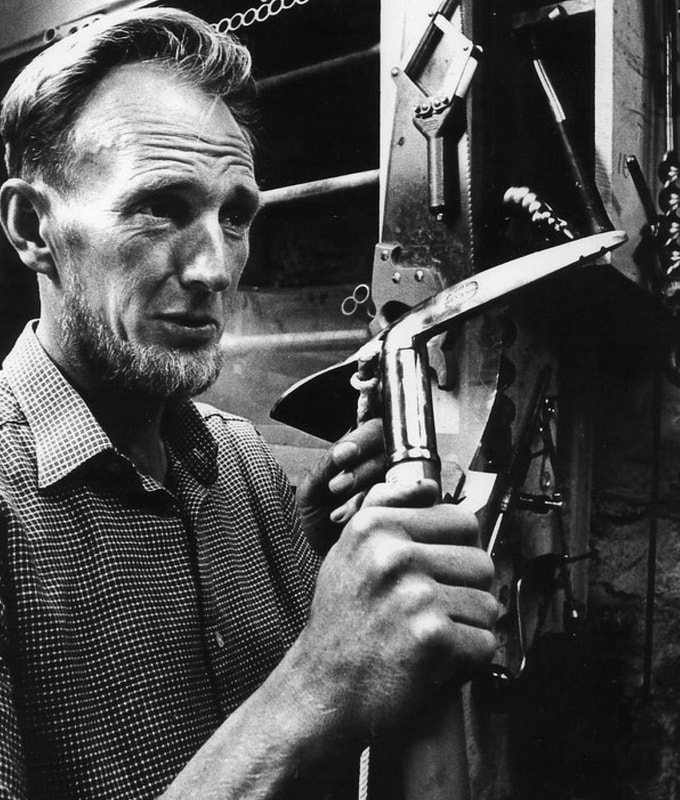

After a long and remarkable life, Hamish MacInnes died on Sunday at the age of 90. We owe a huge amount of our enjoyment of mountaineering to Hamish. His contribution to mountain culture was immense, his work on mountain rescue was groundbreaking, his personal climbing was cutting edge and his development of climbing techniques made profound changes to how we go climbing. It's no exaggeration to say that the modern ice climbing technique of using two ice axes and steeply inclined picks was developed in Lochaber and Hamish MacInnes was at the forefront of this. His “Terrordactyl” ice axes led the way in metal shafted ice axes with inclined picks. We still use this technique today. Way back in 1957, Hamish made the first ascent of Zero Gully on Ben Nevis. In the years following his ascent, several others tried the climb and there were some fatal accidents, often caused by wooden shafted ice axes breaking in a fall. Hamish was driven to engineer the first metal shafted ice axes, which he worked on in his workshop in Glencoe. In the winter of 1960 Jimmy Marshall and Robin Smith completed the most significant week of climbing ever achieved in Scotland. Orion Direct, Smith's Route, Minus Two Gully and the first single day and free ascent of Point Five Gully were amongst the seven climbs they completed on consecutive days. All of this was achieved with a single ice axe each and crampons with no front points. Ten years later in 1970 Yvon Chouinard made a brief visit which was to trigger a change that would revolutionise winter climbing. Using prototype curved ice hammers he made some very fast ascents demonstrating how to climb ice by direct aid, hanging off the pick itself embedded in the ice. Comparing techniques with Hamish MacInnes, John Cunningham and others, modern ice climbing was born. That year Hamish MacInnes developed "The Terrordactyl", a short, all metal ice tool with a steeply dropped pick. The "Terror" and Chouinard's ice hammer dominated the forefront of international ice climbing for several years. Eventually these two designs were combined to create the banana pick which is still the basis for modern ice tool design. Fifty years later, we are still using the same techniques and style of picks. Hamish had a hand in setting up Glencoe Mountain Rescue Team, Search and Rescue Dogs Association and Scottish Avalanche Information Service. His rescue stretchers are still the favourite design of many teams in the UK. He ran the Glencoe School of Winter Climbing, making many first ascents of climbs in doing so.

We owe a lot to Hamish. His legacy will be very long lived. In 2020 Abacus Mountain Guides turned 20 years old, so to celebrate we headed down to Polldubh in Glen Nevis. Not to go climbing, but to plant trees!! Today we planted 20 beautiful little Scots Pines around the Polldubh crags as our way of giving something back to this spectacular environment that we use every day to make a living, as well as being a little "Happy Birthday to Abacus!" The trees we planted are part of Nevis Landscape Partnership's Future Forests Project which began with the pine cones being collected from mature Scots Pines growing just across the river on the opposite side of Glen Nevis. Those old trees are a remnant of the Caledonian Pine forest which once covered large parts of the Highlands, but for various reasons there are now only small pockets left. The pine trees struggle to regenerate due to grazing pressure, predominantly from red and roe deer, so they need to be protected if they are going to grow successfully. Fortunately for our birthday trees they are safe inside various exclosures where no deer or sheep will be able to nibble them, and hopefully in a few decades time there will be plenty of big, strong pine trees on the slopes of Glen Nevis which are regenerating and continuing the growth of the forest themselves. The environment needs our help now more than ever, and at Abacus we believe that we should be giving something back to the mountains and glens that provide so much for us. This is why we will continue with our tree planting and make it a yearly event so we can see healthy, living habitats full of biodiversity continuing to grow.

Back in July we wrote about how hard it is to climb Ben Nevis in the summer (which you can read here). With winter rapidly approaching, how about climbing the UK's highest mountain while it is coated in snow and ice? There are many mountaineering and climbing routes on Ben Nevis, but only one straightforward route, the mountain track, and that is the one we are talking about. The mountain usually sees it's first snowfall in September and it can be in winter condition all the way through to May. So don't be fooled by a warm, sunny April day down in Fort William, the top of the mountains could still be experiencing serious winter weather!

Can you climb Ben Nevis in winter? Yes, of course. However, you need to know exactly what you will be getting into and be well prepared, both in terms of the kit you carry and the skills you will need to look after yourself. Climbing Ben Nevis in the winter months is definitely not for everyone. It can be a long and tiring day, requiring a good level of fitness, and the weather conditions can be incredibly tough, with strong winds and poor to zero visibility on the upper parts of the mountain being quite likely. But if you get it right, successfully reaching the summit and getting safely back down brings a huge sense of achievement. How hard is it to climb Ben Nevis in winter? This can vary massively from day to day, and it depends on the the snow conditions underfoot and what the weather is doing at the time. The bottom half of the track is often clear of snow, with the snow line usually sitting at about 600m. From this point you should expect to be on snow all the way to the summit and back down. After a fresh dump of snow it will be very soft, and if there is a lot of it you will be doing a serious amount of wading. This is incredibly tiring and if you are with friends make sure you take turns at the front so it is not the same person doing all the trail breaking! If the snow has been through some freeze-thaw cycles (meaning the temperature has risen allowing the snow to go soggy, then the temperature drops again, freezing the soft soggy snow into snow-ice) it will be very hard and icy, so the walking will likely be easier but crampons and an ice axe will be essential. Once on the snow you need to be comfortable using your boots to kick steps if it is just small areas of hard snow, or confident walking in crampons on relatively steep ground. Make sure your crampons are correctly fitted to your boots before you set off - the side of a mountain in 40+ mph winds and swirling snow is not the place to be adjusting them. Crampons have a habit of catching on everything - rocks, trousers, your other crampon, you name it - so make sure you practice walking in them on easier ground first. You should also have your ice axe, and know what to do with it. It can be used to provide support while you walk and also to stop a trip or slip from having dire consequences. A clear summit on Ben Nevis is a rare thing so expect cloud, and in the winter that means your navigation needs to be on point. In summer there is a path to follow but in winter this gets completely buried in snow, and there can be little to no difference between the ground and sky. You need to know how to take a bearing from your map, and then be able to follow it accurately on varying terrain. Once on the huge and featureless summit plateau there are cairns to aid navigation but it is common to not be able to see from one cairn to the next, or in heavy snow winters some of them get completely buried. You will still need to follow a bearing on your compass and know exactly when to make the left turn toward the summit. When you reach the summit remember that you're only half way there and you will then need to do everything in reverse, so stay switched on all the way down. How long does it take to walk up and down Ben Nevis in winter? This depends on a number of factors but on average it takes between seven and nine hours to climb Ben Nevis in winter. If you are fit and experienced, and you get good snow conditions you could be quicker, but you should plan to be out for an entire day. With a lot of fresh snow it could take upwards of 10 hours, and remember that in December and early January there is less than seven hours of daylight. Do I need crampons for Ben Nevis? If you are climbing Ben Nevis between November and early May then you should plan to take crampons and a single mountaineering ice axe. Early in the winter season the snow cover will be thin and it will come and go, but it doesn't take long for the snow to build up and for crampons and an axe to become essential. You don't know if the snow will be hard and icy until you are up there, by which pioint it is too late to go back and get them! They need to be real crampons rather than microspikes, which are next to useless on hard, icy snow. Your crampons need to be fitted to winter boots, either B2 or B3 rated. Winter boots are much stiffer than summer boots which means you get a lot more support, you can use the edge of the sole to kick steps in the snow and your crampons will stay on. Soft summer boots bend inside crampons and the crampons simply fall off. Another essential piece of kit is a pair of goggles. When the snow is being blown into your face and you are trying to walk on your bearing you will find goggles absolutely vital. See the video below for a run down of essential winter kit and our full Ben Nevis in Winter Kit List is here. Is there snow on Ben Nevis all year round? Yes and no. Some of the deep gullies on the North Face can hold snow all year round but on the western side of the mountain where the mountain track is, this is not the case. The first snow usually falls in September with winter kit normally required between November and early May. The top of Ben Nevis is often hidden in cloud so you could look at the first 1000 metres and think there is no snow without realising that the top 300 metres is still very wintry. Do your research and make sure you go prepared. Is it dangerous to climb Ben Nevis in winter? Any mountaineering activity has it's risks but it is possible to minimise these risks and have a fantastic day in the Scottish mountains:

Moving up to the next grade can feel like a daunting prospect, or sometimes an impossible leap. Much of the time the barrier is in our heads but there are also some practical steps you can take to reach the next level in your winter climbing. Here are some practical things you can do to help. Protection To get used to placing protection on harder climbs and in more difficult positions, when you are climbing at your current grade place protection in tricky places. You know you can climb at this grade and you can place protection in comfortable places. As well as this, stop on the steeper, trickier sections and place protection. Don’t power through the crux; instead stop half way through it and place an ice screw or a nut. This will give you practice in placing protection in more difficult places which is what it will feel like on the harder climb. Make sure you are relaxed and slick at placing the protection. If it does not work you can just carry on climbing like you would have done anyway. In fact, even if you don’t place protection, stopping half way through the tricky section of your current grade is a good idea. Instead of powering through, rushing through the crux to easier ground above, slow down, stop and admire the view. You need confidence in what you are doing and in the position you are in. If you are rushing though the crux you are not ready to move up a grade. If you are relaxed and confident enough to stop and soak up the atmosphere, to admire the view, you are ready to try a harder climb. You need to trust your protection and belay anchors. You might even need to do a hanging belay on the next grade of climb. So, practice and get confident in your anchors by leaning out on your anchors when you are belaying your buddy. This is a good idea anyway. You do not want any slack rope between you and your anchors if you are belaying off your harness so that there is no chance of a shock load on your anchors if your buddy falls off. So, kick out a nice ledge, stand tall and lean back on your anchors with confidence. Research Do your research. Winter climbs come in all shapes and sizes, styles and characters. Choose one that matches your strengths, whether it is ice, mixed or snowed up rock. Find out what it takes to be in optimum condition, where the pitches go, where to belay and where the crux is. Choose a popular climb which is well known, not an esoteric adventure that has only seen one ascent. Make sure it is well known so you can get the information you need, and so you know the grade is accurate. You will also be able find out when it has been climbed recently which is quite a reassurance. Making the first ascent of an ice climb each winter is certainly more nerve-wracking than climbing it after many recent ascents. Having said this, it can be tricky working out what kind of route each one is and therefore what the optimum conditions are. The information is much more available these days though, and don’t be afraid to ask around. Experience Climb with climbers who are better than you. You will find it easier to move up a grade if you have seconded a few climbs at that grade and you know what it feels like. In fact, if you can get a buddy to lead you up a climb that you want to lead yourself you will have much more chance of success. Much of the difficulty in moving up a grade is psychological so take away the concerns over route finding, where to belay, what kind of protection to take with you as well as the climbing itself by climbing it with a stronger climbing buddy. Even though leading a route you have seconded makes it much easier to lead, you will still have the confidence of having lead at that grade which will carry you forward to your first onsight lead of that grade. Serve an apprenticeship and move through the grades steadily. If you climb one grade IV route you are not automatically ready to climb a grade V. Even if you find the grade IV straight forward you should climb several more at that grade before moving up the grade. Experience is earned through spending time on lots of climbs in different locations, on different days and in different conditions. You learn how to deal with many, many different situations and these help you cope with new situations that you will undoubtedly face. “There is more to ice climbing than climbing ice”. In fact, the techniques of winter climbing are only a small part of climbing winter routes. Be prepared to build up a huge bank of experience by climbing lots and lots of routes. You will learn all sorts of tricks from other climbers, about dealing with the harsh weather, about how the weather affects the climbing conditions, about avalanche safety and navigation, and about how to cope with all the little (and some major) things that don’t go completely right every time! System

Sort your system so that you stay warm and dry. We all have different preferences of gloves and clothes but a system that works well for you is essential. Any fool can be cold, hungry and dehydrated but all these will reduce your performance. Play around with different gloves and carry spares for when you get wet. Use a belay jacket, one between the two of you if you are swinging leads. A jacket that fits over your helmet, that does not pull out from under your harness and that does not hang over your harness covering up your gear makes a huge difference to your climbing. Find food that is easy to eat on a belay ledge and something to drink in something you can drink from easily. If you can arrive at the foot of the crux pitch feeling warm, dry and well fed you will be in a much better position to climb it. The concept of marginal gains really makes sense to me in winter climbing. Making sure your zips are done up really can help you climb the next grade! |

AuthorMike Pescod Self reliance is a fundamental principle of mountaineering. By participating we accept this and take responsibility for the decisions we make. These blog posts and conditions reports are intended to help you make good decisions. They do not remove the need for you to make your own judgements when out in the hills.

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed