|

You know those white rocks you see every now and then when you're walking in our mountains? They are made of quartz, one of the coolest things ever! They can form beautiful crystals, they resonate when you put an electric charge across them, they create an electric charge when you squash them and it is possible to melt them in a very, very hot fire to weld other rocks together (although we can't work out how!).

Quartz is the most abundant and widely distributed mineral found on the Earth's surface. It is found everywhere and is plentiful in igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks. It is very durable, resisting mechanical and chemical weathering. As a result, it is very often found on mountain tops and is the primary constituent of beach, river, and desert sand.

These are some quartz crystals I found in the Alps. Quartz is one component of granite, along with mica and feldspar. When granite cools down incredibly slowly, the minerals have time to come together to form big crystals. The slower it cools, the bigger the crystals. Some quartz crystals are 50cm long and crystal hunters still work in the mountains of the Alps. Quartz is a chemical compound made up of silicon and oxygen (SiO2 - silicon dioxide or silicate) and the molecules are perfectly lined up in a crystal, in the same way that carbon atoms are lined up in diamonds.

So, why is the quartz we see in our hills white, and not crystaline? Well, imagine the crystaline quartz is a car windscreen. When you hit it, what happens? It fractures along lots of lines that criss-cross and make it look white. It's the same with our quartz. It has so many imperfections in it, so many fractures and layers, that the light going through it is refracted and reflected inside, making it look white.

Watches used to advertise the fact that they rely on quartz. Quartz resonates (vibrates) at a specific frequency when you pass an electric charge across it. It is possible to use this resonance at a known frequency to set the speed of a watch. The frequency does not change, even when the electric charge changes so it is a very reliable method to use for measuring time.

Quartz is a pietzoelectric material. This means it creates an internal electric charge when you apply mechanical stress. Squash quartz and you can make an electric charge sufficient to cause it to spark. You have probably done this when you light a gas stove. Jetboil stoves have them; the little button you press squashes a pietzoelectric material to make the spark.

Sitting high above Glen Nevis, Dun Deardail is one of Scotland's 70 ancient vitrified forts. There are very many hill forts, but the vitrified forts are different in that they have been burned at a very high temperature for enough time for the rocks to melt and stick together.

The process of vitrification occurs when a timber-framed drystone rampart is destroyed by fire. With temperatures reaching over 1000° C, the heat from the blaze begins to melt the rubble core of the rampart. As the burning rampart collapses, the rocks first fracture and then become liquid. Gas bubbles form inside the rocks as the extreme temperatures change their mineral composition. When the fire burns out and the rampart finally cools, the burnt and molten rocks form large blocks of conglomerated stone. These can still be seen within the rampart. Vitrification is not a deliberate construction method as the original timber-framed drystone rampart would have been more stable; it is much more likely to have been the result of accidental fire or deliberate destruction. In recent excavations coordinated by Nevis Landscape Partnership, rocks of different types were found stuck together with quartz. The Fort from Nevis Landscape Partnership on Vimeo.

So, next time you see some white rock, stop and look to see if it is quartz. Wonder at its amazing properties. Look to see if it is slightly transparent and crystaline. Imagine finding a crystal cave in which the walls, ceiling and floor are covered in quartz crystals, hundreds of millions of years old, that took millions of years to form. Be amazed by its electrical powers. Quartz is cool.

2 Comments

A traverse of the Cuillin Ridge is a classic expedition that many people aspire to. What most people underestimate is just how big a challenge it is and how well it measures up to anything else in the world. It is truly world class. We certainly can't go to the Cuillin Ridge on Skye right now, but this might be a very good time to do some planning for when you do go there. April, May and June often offer the best conditions to be there; settled weather, dry rock, light winds and even one or two old snow patches from th winter to offer a supply of water. A traverse of the full ridge often starts with Gars Bheinn on the south end and goes north to finish on Sgurr nan Gillean. Return The walk out will feel far longer than it really is but you do eventually reach the Sligachan for a well earned celebration. Length Gars Bheinn to Sgurr nan Gillean is 11km including the short extra bits to get to Sgurr Dubh Mor and Sgurr Alasdair. There’s also 1750m of ascent going along the ridge. Add on to this the walk in (2.5km and 895m ascent from Loch Scavaig) and walk out (5km to Sligachan) making it 18.5km with 2645m ascent. Grade The exact route taken is open to much variation and you’ll need to decide your rules of engagement. Taking all the easiest options means there are several sections at grade Difficult that must be climbed and a few abseils. Optional extras include the TD Gap (Hard Severe), King’s Chimney (Very Difficult) and Naismith’s Route (Very Difficult). Guidebook and Map The SMC guidebook “Skye Scrambles” has a good description of all the individual sections as well as good diagrams. Andy Hyslop’s mini guide to the ridge is possibly the best resource to have though. The Harvey’s map “Skye The Cuillin” is the best map and is printed on waterproof paper. It’s at 1:25,000 but has the main ridge at 1:12,500 scale and also describes common routes on the sides of the main ridge. Valley Base The logistics can be awkward down to the single track roads and the length of the traverse. Two cars are often necessary and being based at Sligachan is probably best. Leave one car here and drive to Elgol to take the boat to Loch Scavaig. If it all works out you will get back to Sligachan after the traverse. However, if you escape off the ridge early you will end up in Glen Brittle a long way from your car. Approach Going from South to North as is most common in the summer, you have two options. From Glen Brittle camp site it is best to walk up the well made path to Coir a’Ghrunnda. There is good water here so you don’t have to carry any for the two hour walk in. A short boulder slope from the west end of the loch takes you to the crest of the ridge. Dump the bags and go out to Sgurr nan Eag to start your traverse from there. The better option these days is to take the fast boat from Elgol to Loch Scavaig. You can ask to be dropped off on the west shore for the easiest route up to Gars Bheinn where purists will say you have to start anyway. This approach has the added dimension of a boat trip making the whole enterprise feel that much more adventurous, and is recommended. Route Summary There is far too much detail in the 11km along the ridge to include much of a description here. There is continuous scrambling and occasional sections of rock climbing. Getting along the ridge involves more route finding skills than navigation and it takes a while to get used to the structure of the rock to choose the best route. There are a few sections where time can be saved (or lost) with a bit of knowledge of the best line to take so spending a few days scoping out these sections is time well spent. In the mist, completing the traverse is all but impossible without prior knowledge of the best line. Sections to scope out include – Sgurr nan Eag and Sgurr Dubh Mor. Sgurr nan Eag involves only very simple scrambling if the best line is taken, this being on the west side of the crest. Sgurr Dubh Mor has a complex line that is particularly confusing in the mist. You can lose a lot of time in the TD Gap so it might be worth doing this with your rucksack on or practicing hauling your packs. It’s good to know how to avoid it as well in case it turns out to be wet – traverse under the west side of the TD Gap on a trail in the scree to the Bad Step of the south west ridge of Sgurr Alasdair. Scramble up this and reach the top of Sgurr Alasdair. Sgurr a’Mhadaidh and Bidein Druim nan Ramh are complex peaks, each with several tops. The central peak of Bidein usually requires an abseil to descend and finding the abseil point is tricky as it is not obvious. There's also the Belly Ledge on An Casteal to avoid, so a day spent going from An Dorus to Bruach na Frithe would be very useful. Best tactics for a complete traverse Spend some time on the ridge before you set out on your traverse. The Cuillin hills are unique in the UK for their continuously rocky nature and the relentless exposure on the crest of the ridge. It’s the never ending concentration required that is so draining for most people and getting used to the scrambling both up and down will help with this. By moving efficiently and confidently on exposed sections you’ll save lots of energy, both physical and mental, so get some long days in on the ridge first. Set your rules of engagement. What is your objective? To reach all eleven Munros? To get from end to end? To do these and to climb the TD Gap and Naismith’s Route? Make sure you agree your objectives with your partners but be prepared to change these if the weather does not work out as expected. Decide whether to bivi on the ridge. Watching the sun set over the sea from a camp on the crest of the ridge and scrambling on the ridge in the early hours of the next day are great experiences. The down side is carrying the extra gear required. Going light and fast is great, as long as you do move fast. Even then you should expect one of the longest days of mountaineering you’ll ever do. Another idea if the forecast is good, is to have a big dinner then walk up in the evening to sleep on the ridge. You’ll have less to carry then and will have a head start on the traverse. Water is a problem. There are very few places to fill up with water and in hot dry weather you will need to drink a lot, especially if you bivvy over night. Find out where you might find water, look for these places in advance, plan your bivvy spot around the availability of water. I know of many attempts that have failed due to lack of water. This is the toughest single mountaineering challenge in the UK, so it’s always going to be valued very highly. However, there is so much more than this.

Being on an island and rising straight out of the sea makes the setting outstanding. Sections of the ridge require you to stay absolutely on the crest with the full drop down to the sea on one side and down to Loch Coruisck on the other. The nature of the volcanic rocks is fascinating, following stepped dykes sometimes and crossing the many gaps where dykes cutting across the ridge have eroded. The combination of all these makes it very special but it’s even more special because you have to work hard and have some good luck to complete a traverse. As with most things, the more you have to work to achieve something, the better the reward. During the current lockdown, lots of people are walking more than before, and more frequently. New places are being discovered close to home that bring people into contact with nature, and for more lucky people totally immerse them in nature. Hopefully this will be one of the positive outcomes of the lockdown that we keep going on the other side of covid-19. Walking is very, very good for all of us. You don’t have to take my word for it. There’s a book I’d like you to read called “In Praise of Walking” by Shane O’Mara. Don’t be put off by the evangelical sounding title; it’s a fascinating read, very well referenced and backed up by scientific research, all about the astounding benefits of going for a walk. The physical benefits of walking are very well understood. Regular walking brings positive changes in virtually every single measure of health including a drop in body mass index, a reduction of measured body fat as a percentage of total weight, a decrease in triglycerides thought to underlie some forms of heart and cardiovascular disease and an increase in production of heart loving fats called high-density lipoproteins. It works for everyone and the more you walk the more the benefit to physical health. The message is, if you need to lose weight and want to look after your heart, go for a long walk, as often as you can, ideally through nature and ideally build it into your daily routine. Bizarrely, walking also makes us more intelligent. We know this by studies using the Stroop Test, a very simple method of evaluating cognitive performance using words written on paper in different colours. You would have thought that the cognitive demands of standing and walking would reduce the brain’s capacity to do more tasks. This is not the case. Standing and walking improve our cognitive performance, as demonstrated by the Stroop Test. Most of us who walk regularly understand this very well. We often think more clearly when we are walking, engage in interesting discussions and have our most creative thoughts. Philosophers have often commented that they can only think when they are walking. Not only does walking improve the performance of our brains, it strengthens the physical structures of the brain. Studies on old people have shown that regular walking can reverse the effects of aging on the brain, making it two years “younger”. Simply by going for a walk, we make our brains stronger and more effective. However, the most important benefit of walking is that walking in the natural environment has profound restorative effects on our wellbeing. “Attention Restoration Theory” tells us that the human experience of the natural world markedly assists in maintaining and fostering a strong sense of subjective wellbeing. Modern day life in our urban, man-made environments, increases mental fatigue, stress and anxiety. Restoration of feelings of calm, relaxation, revitalisation and refreshment can be achieved by spending time in a natural environment. For it to be most effective, a natural environment should have three critical elements;

Going for a walk is perfect! Removal from Normal Life I’ve often said to people, walking is like meditation. We are removed physically and mentally from our everyday lives. We get so involved in the moment, in the activity and its demands on us, that we very often forget all about our normal worries and anxieties. The more we are challenged by the activity, the less cognitive bandwidth we have for anything else. It’s only when we get back home that we remember about the outstanding bills, the anxiety caused by our work or any number of things that cause our mental fatigue. Fascinating Sensory Elements It’s really obvious that our landscape is full of astounding visual and sensory elements that are fascinating, beautiful, full of wonder and surprising. Over the last few years I have increased my knowledge of the natural environment massively, especially through projects such as The North Face Survey on Ben Nevis. It’s also clear to me that there is a never-ending supply of new knowledge to gain, new insights to understand and new things to see. This understanding of the very small things in our landscape makes my enjoyment of the vast scale of the landscape even more rewarding. It Should Be Expansive By exploring the landscape that surrounds us in Scotland we get to feel the immense scale of the landscape, the power of the weather, and the never-ending nature of wildness, that can give us a proper sense of scale. On a walk in Glen Nevis, when I find a stone with stripy layers that are bent and contorted I think of the age of the rock and the scale of the forces that resulted in this small stone. The rocks of the Mamores are about 800 million years old. Homo sapiens (us, the human race) evolved about 200,000 years ago making the Mamores 4000 times older than us. The Mamores were south of the equator back then and they have drifted up to where they are now moving at the same speed that your thumbnail grows. They were 10,000m high at one point, higher than Everest is now. The pressure on my stone and the heat required to metamorphose it into the rock it is today were provided by the weight of the mountains and the heat from the Earth’s centre towards which it was pushed. Not everyone is into geology but just with this little bit of knowledge we can get a proper sense of the scale of our landscape and the age of the planet. It is a good reminder that each of us is not at the centre of things with the world revolving around us. We need to learn some humility and to take responsibility for ourselves. This is surely the expansive nature of the experience that is required to make its restorative effects most profound.

This is why I am passionate about spending time on our mountains. It maintains our physical health, it restores our mental health and it can have a profound influence on our spiritual well-being. It can counter the self-centred focus that modern day life has on us all. In these days of global climate change, an obesity epidemic, mental ill health and disconnectedness from nature, one solution is simple. Go for a walk, preferably a long one and immerse yourself in nature! Scotland has enjoyed enlightened access rights for seventeen years. The Land Reform Act of 2003, and the Outdoor Access Code that goes with it, gave us all the right to responsible access of any land other than gardens and industrial land. No other country in the world has such a good system that works both for landowners and for people seeking access. We can go walking, climbing, cycling, horse riding and camping on the land, kayaking, canyoning and swimming in the rivers. We can do just about anything that is not powered by an engine and that is responsible. It's this key phrase, responsible, that is what makes this legislation different to any other access legislation, and what makes it work so well. Our access legislation does not mean we have the right to go anywhere, in any way we like, to do what we like. Instead, it means we need to consider what is responsible, what will be the impact on other people including the land owner, other users and the population as a whole. We need to be considerate of other people, not selfish, when we exercise our right of access. Climbing has been described as fundamentally selfish, it is of no benefit to anyone but the climber. Climbers often express the anarchistic side of their nature through their climbing, the rebelious urge to break rules, in fact the desire to play in an environment that does not have rules. Considering other people and being responsible are rarely our first considerations but the risks of accident and injury do impact our friends and family, and the nation as a whole when we rely on rescue services and the NHS. How can we justify going climbing if it is fundamentally selfish and, potentially, costly to the nation? Each time there is an accident in the mountains that reaches the media, people describe the climbers as "selfish", "suicidal", "unjustified" and calls are made for them to pay for their rescue and medical treatment, for climbing to be banned, for our access rights to be taken away from us. Very prominent people in government say these things on radio discussion programmes. After all, if a small change in our access rights that affects a small number of people in our population might save a few lives and the cost to the tax payer, it would be worth it, right? Well, no. It would be a disaster. The benefits of climbing might not be quite as tangible or immediate as the very occasional accidents, but they are very powerful and benefit all of society. I've mentioned the benefits of climbing in several previous posts. They include physical health, mental health, spritual well-being, a proper and personal sense of risk assessment, a time of separation from our daily anxieties, immersion in nature and a sense of well-being that comes from connectedness with nature, respect for other people and a clear demonstration that, in the most basic of things, we are all equal. We go climbing to remind ourselves what matters in this world. When enough of us benefit from these things, society as a whole benefits, and our selfish acts of climbing become beneficial to to the rest of society. "Normal" life that includes everything that is designed to make life easier for us, simpler, more comfortable and more pleasurable, leads to a more self-centred way of living. Climbing does the opposite. Climbing grounds us, reminds us of what matters in this world, makes us less self-centred. A lot of us are thinking about what matters in life right now as we deal with the COVID-19 emergency. A lot of us would really like to go climbing right now to help us deal with the very stressful situation we all find ourselves in. However, this is not the time to be anarchistic or to make decisions based on our personal risk assessments. Instead, right now is the time to demonstrate how responsible we can be when there is a requirement to do so. We have the right to responsible access, and to be responsible right now means we can not travel to do our daily excercise (not even five minutes in the car to a nearby walking area), we must stay at home, work at home if at all possible and stay apart from other people.

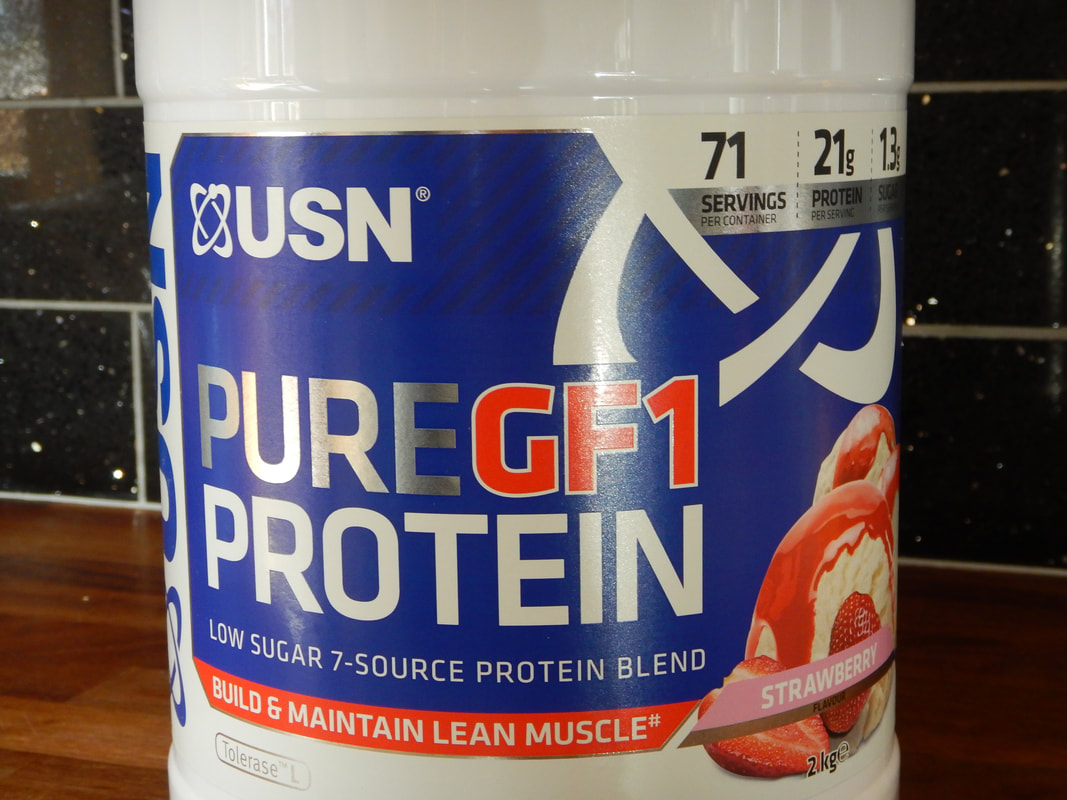

This is a temporary situation and right now it is more important than ever to maintain good relationships between neighbours and within communities. This is not about restricting the general right of responsible non-motorised access to land but it is part of the wider approach to prevent COVID-19 deaths and preserving the nation’s food supplies. Most of us are doing the responsible thing, and all of us are looking forward to things going back to normal so we can go climbing again. However, I'm sure, like me, you are all questioning why we can't go climbing right now. Hopefully, this will help. Here's the Ministerial Statement on Access Rights that very clearly explains what is expected of us and why. Coming home from a big day of climbing I used to feel a real slump in energy. This isn’t very surprising really, a day on Ben Nevis is hard work and uses a lot of calories, so feeling tired at the end of it makes sense. It was a pain though - I come home to a chaos of children and their after school activities, phone calls and messages, Louise telling me about her day and all the jobs I need to do such as drying my gear, checking forecasts and trying to work out where to go tomorrow, when all I wanted to do was collapse on the sofa. I wanted a way to avoid this dip in energy and nutrition seemed to hold the answer. Back then my strategy was to eat more. On a really big day I’d get a pack of five jam doughnuts and eat them all before eating a regular dinner later on. Instant sugar energy would pick me up, right? And I do so much exercise that the calories would be burned off the next day. As nice as this was, it wasn’t working. A few friends were talking about a ketogenic diet like what Dave MacLeod has used successfully for a few years now. After completing his 24/8 project (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=huL5TdBfTIE) Dave talks about finishing this amazing athletic feat feeling that he could carry on going. He describes feeling a uniform supply of energy, no peaks and troughs like you can get on a diet of carbohydrates. Looking more closely at the ketogenic diet, I could not work out how I could get it to work for me. You can’t have cereal for breakfast or sandwiches for lunch. The practicalities, cost and dedication to follow it when the rest of my family was eating very different meals made me look elsewhere. This is when I was lucky enough to hear some advice from Rebecca Dent, the High Performance Dietician, aimed at British Mountain Guides, with the aim of helping us stay fit and healthy enough to carry on climbing right through our careers and into retirement. Having taken her advice and acted on it, I realised half way through this winter that I do not now suffer the big energy dip I used to when I got home. It was a hard winter with lots of tough days. The only change I have made is in my diet, so I can only attribute the results to this. The advice included a few things. In short; eat more protein, more omega 3 oil (found in oily fish), lots of vegetables every day and half of these should be green, berries every day, nuts and seeds, and beetroot juice. We should also eat protein in all our meals and eat lots of small snacks instead of a few big meals. Here’s great article written by Rebecca giving an example of what to eat and when to eat it on a big day of climbing - https://www.rebeccadent.co.uk/nutrition-articles/2018/2/6/nutrition-tips-for-long-mountain-days When we are working hard, day after day, we need more protein. The recommended intake for a normal lifestyle is 0.8g of protein per kg body mass. When we are working hard we should increase this to about 1.6g per kg body mass. As a guide, an egg contains about 13g of protein, a chicken breast of 172g has about 54g of protein. My body mass is 85kg so I need to take in about 136g of protein each day which is quite a lot. We can get protein from meat, fish, eggs and dairy such as yoghurt. Nuts also have a lot of protein but we need to be wary of eating too much saturated fat that you get a lot of in nuts. Protein powders are very useful (like what bodybuilders use). I found there is a huge range of these and it is really hard to know which to go for. Find one with whey protein and creatine (3g per day), and a second one with casein (30g to 40g per day, best just before bed time). Omega 3 oil is found in fish such as salmon, sardines and mackerel (but not tuna, cod or haddock - fish fingers don’t count!). If you don’t like fish you can take fish oil tablets - three of the 1000mg tablets every day when you are exercising hard. Do you get your five portions of fruit and vegetables each day, every day? Each portion is 80g and the total is 400g (minimum) each day. Half of this should be dark green vegetables such as sprouts, spinach, broccoli, kale, cabbage etc. Your dinner plate should be half covered in vegetables and half of these should be dark green. You can look up the reasoning behind all these things, there’s too much to put into this article. The next step is to work out how to build this into your daily diet and routine. Don’t go for one big change, a complete overhaul of your food intake. Instead, make small changes over a period of time and work out what you can sustain. It’s hard to maintain a revolution, easier to make small changes in your daily habits. Here’s how it works for me. Breakfast - granola style cereal with yogurt, berries and toasted seeds and nuts. Packets of frozen berries are not so expensive and I make yogurt at home (see below). Lunch - sardine sandwiches made with seedy, wholemeal bread with sardines in tomato sauce (35p per can) and a little extra tomato ketchup, eaten over three snacks during the day. Back at the van - protein shake plus an apple and a pear. When I get home - peanuts or mixed nuts. Dinner - a source of protein, lots of vegetables and some brown rice or pasta, potatoes etc. Supper - a slice of seedy, wholemeal bread with peanut butter or a bowl of granola cereal with yoghurt. If you’ve climbed with me during the last year I probably went on about sardine sandwiches! I used to eat cheese, butter and mayonnaise sandwiches. By cutting these out and replacing them with sardines, I’ve cut out a lot of fat and replaced it with a cheap source of protein and omega 3 oil. It helps that I like sardine sandwiches and I’m aware that not everyone does! I try to cut out as much refined sugar as I can. No more doughnuts (at least, not very often!), no sugar in my tea, no sweets and I prefer dark chocolate. As for carbohydrates, I try to eat good quality carbs (brown rice instead of white, brown bread, sweet potatoes instead of regular spuds), and I try to match my intake with the exercise I do. The last two weeks have seen my level of exercise drop dramatically so I have reduced how much cereal, bread and rice/pasta I eat. My diet is not perfect, not by a long way. I still eat biscuits, cake, fish and chips. But I’m more likely to reach for a protein snack instead of doughnuts, I eat a lot of spinach, and I eat sardines most days. The result is that I don’t have that dip in energy levels when I get home and, long term, I should have fewer niggling injuries and be able to keep on climbing for another thirty years. I’m 47 now, and I wish I’d done this 20 years ago! Here's how to make yogurt.

I use an Easiyo tub to make it in. This is just an insulated tub which holds enough boiling water to surround the 1ltr container and keep the heat in for several hours. If you don't have something like this you can heat the milk and make the yogurt in a vacuum flask, or keep it warm in a warm slow cooker or even just on a radiator. I mix up 1ltr of full fat milk with 1tbs live yoghurt (Yeo Valley Natural Yogurt) and 2tbs full fat milk powder in the container. I place this in the big tub with boiling water and leave it over night. It's as easy as that. Without the insulated tub, heat 1ltr of full-fat milk over a medium-low heat until almost bubbling (85ºC), stirring often so it doesn’t catch on the bottom. Leave it to cool enough that you can stick your finger in it but it’s still pretty hot (46ºC). If you want to get more accurate, use a thermometer. Then mix in the yogurt and milk powder and keep warm and still for at least 5 hours. Once started, you can use a spoon of the old yogurt to start the next batch. One of my favourite post-workout snacks now is yogurt with berries and protein powder. It's filling, very tasty and really helps with the recovery. |

AuthorMike Pescod Self reliance is a fundamental principle of mountaineering. By participating we accept this and take responsibility for the decisions we make. These blog posts and conditions reports are intended to help you make good decisions. They do not remove the need for you to make your own judgements when out in the hills.

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed